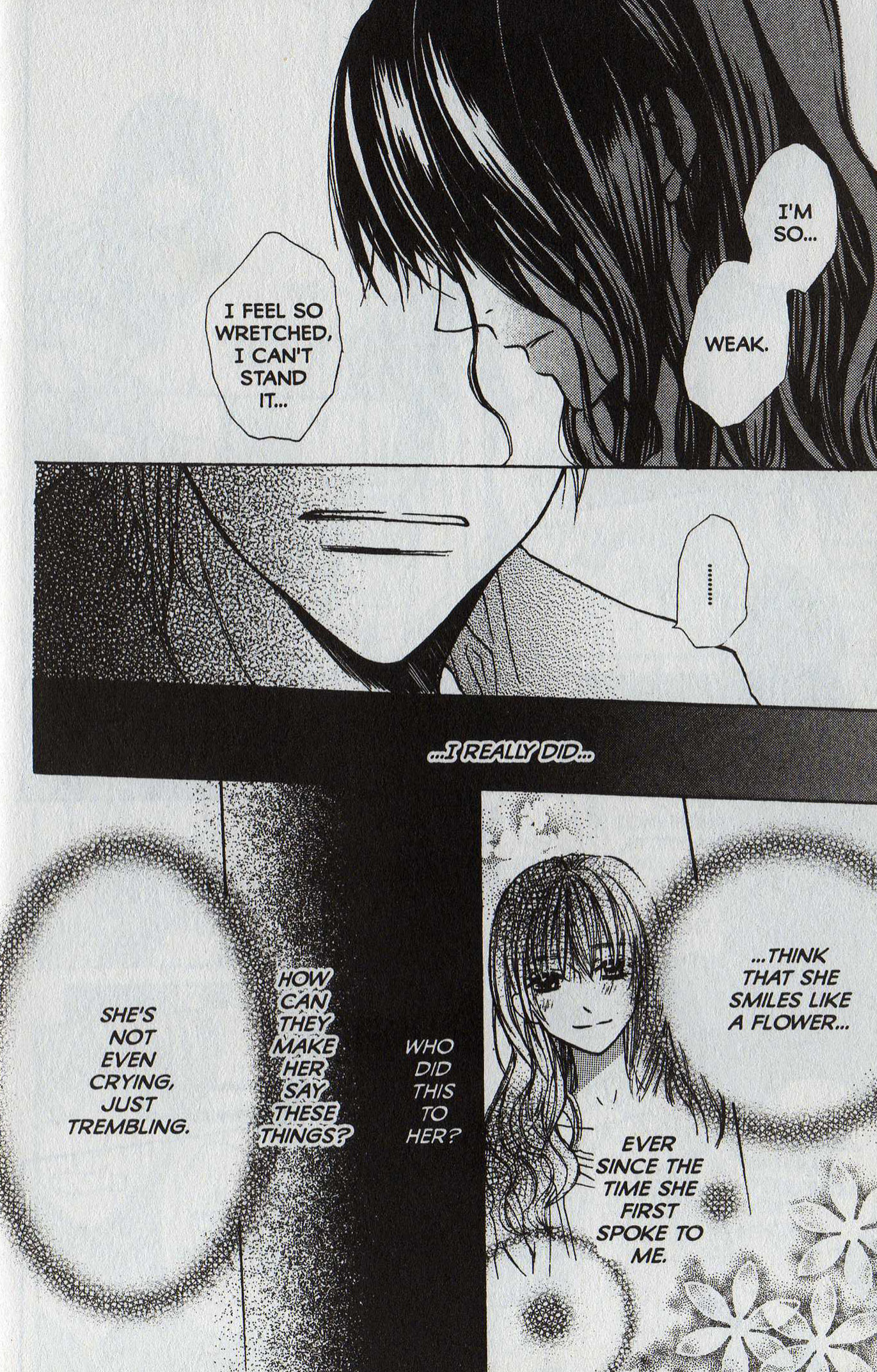

Mohiro Kitoh’s Bokurano: Ours (Viz) is one of those comics that apply grimly serious coats of paint to popular fantasy architecture. In this case, it’s about a group of kids climbing into a giant robot to save the world. The twist is that the kids are realistic, or “realistic,” in that some of them are understandably frightened or emotionally disturbed or just plain awful instead of sunny and dedicated. There’s also some play with what would actually happen if giant robots battled in a populated area.

Mohiro Kitoh’s Bokurano: Ours (Viz) is one of those comics that apply grimly serious coats of paint to popular fantasy architecture. In this case, it’s about a group of kids climbing into a giant robot to save the world. The twist is that the kids are realistic, or “realistic,” in that some of them are understandably frightened or emotionally disturbed or just plain awful instead of sunny and dedicated. There’s also some play with what would actually happen if giant robots battled in a populated area.

It’s a competent comic, but it isn’t particularly interesting to me. I’m not a fan of un-deconstructed giant-robot stories in the first place, and I’ve never yearned to see anyone expose their seedy underbellies. And it isn’t as though there’s a shortage of bleak versions of kid-friendly concepts, so I can pick and choose from the best of them. (Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto, also from Viz, is a great example. Come to think of it, there’s some great giant-robot nonsense in Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys which treats the concept with the degree of seriousness I feel like it deserves, which is just about none at all.)

I’d read the first few chapters of Bokurano on Viz’s SigIKKI site, but it didn’t hold my attention in the way that site’s weirder, more imaginative series have. I thought it might read better in a larger chunk, but I found myself even less attentive. You can’t win them all.

(This review is based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher. You can read a bunch of free chapters of Bokurano: Ours here.)