Hisae Iwaoka’s Saturn Apartments (Viz) is the only title that I’d read prior to its inclusion in the top ten list of the Young Adult Library Services Association’s 2011 Great Graphic Novels for Teens. I can’t help but compare this book to Kou Yaginuma’s Twin Spica (Vertical), which earned a place on the main list. I like them both a lot, but I tend to think I’d have argued for Spica to take Saturn’s place in the top ten.

This is mostly because Spica has a stronger underlying narrative. It’s got a clearer arc and digs deeper into its cast of characters. That doesn’t suggest failure on the part of Saturn, as the first two volumes clearly indicate that it has different aims, favoring episodic world-building rather than sequential storytelling. It’s easy to enjoy Saturn chapter by chapter, but it’s easier to become involved in Spica, if that makes any sense.

This is mostly because Spica has a stronger underlying narrative. It’s got a clearer arc and digs deeper into its cast of characters. That doesn’t suggest failure on the part of Saturn, as the first two volumes clearly indicate that it has different aims, favoring episodic world-building rather than sequential storytelling. It’s easy to enjoy Saturn chapter by chapter, but it’s easier to become involved in Spica, if that makes any sense.

In the third volume of Saturn Apartments, Iwaoka seems to undertake the construction of some substantial subplots. Stand-alone chapters give way to small story arcs, and threads start to recur throughout the volume. This is welcome in a way, because it shows an intention to give the series more weight, but it also seems like this kind of plotting may not be Iwaoka’s strongest skill.

After two volumes of beautifully drawn, gentle glimpses into Iwaoka’s orbital world, the subplots feel rather clumsily wedged into the narrative. They aren’t unpromising, but their emergence feels abrupt. It strikes me that none of the supporting characters were yet able to carry that much purpose at the time it was thrust upon them. The eventual (and logical) inclusion of Mitsu in that thread may change that, but the sequences are still hampered by an imbalanced quantity of expository dialogue that’s out of step with the rest of the script.

One thing that does constitute a welcome development here is a slight shift in tone. Iwaoki is also expressing more interest in the class disparities that characterize the culture she’s built. There was nothing wrong with her initial approach, affirming the value of unglamorous work in a society, but it’s nice to see her underline some of the unfairness that keeps her fictional society ticking.

Overall, the series is still one of my favorites. Iwaoki’s graceful illustrations and fragile character designs continue to hold the eye, and the underlying concept is as sturdy and productive as ever. I just wish the shift to a different, more complex kind of story felt less awkward.

(This review is based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher.)

It’s impossible to capture the scale and scope of a disaster like Hurricane Katrina, and a smart creator wouldn’t even try. Josh Neufeld is a smart creator, and he’s a talented one, and I like the approach he takes to

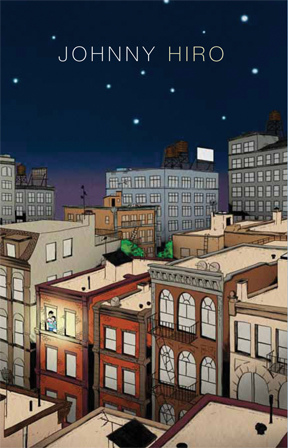

It’s impossible to capture the scale and scope of a disaster like Hurricane Katrina, and a smart creator wouldn’t even try. Josh Neufeld is a smart creator, and he’s a talented one, and I like the approach he takes to  Johnny and Mayumi are young, in love, and living in New York City. That means they work too hard, live in a kind of crappy apartment, and never seem to have enough money at the end of the month. But they have each other and all of the affection, support and loyalty one could hope for; they also have cats. Those things go a long way to compensate for the overworked, underpaid grind.

Johnny and Mayumi are young, in love, and living in New York City. That means they work too hard, live in a kind of crappy apartment, and never seem to have enough money at the end of the month. But they have each other and all of the affection, support and loyalty one could hope for; they also have cats. Those things go a long way to compensate for the overworked, underpaid grind.