I’ve enjoyed a lot of comics written by Greg Rucka, but I have to admit that I haven’t read one in a while. His Whiteout and Queen and Country books for Oni were very good, and I’ve liked some of the super-hero stuff he’s done for Marvel and DC. I thought he did particularly well with stories set in DC’s noir-ish Gotham City, as those comics always had an interesting texture and sense of place. So it’s nice to have the chance to read a comic written by Rucka that has that same feel without the word “crisis” in the title.

It’s Stumptown (back at Oni), a detective yarn set in the Pacific Northwest, and it gets off to a very promising start. It’s got one of those gender-neutral protagonists, a female private investigator with a lot of qualities that could stereotypically be tagged as male, but there’s no reason they should be. Women can certainly gamble too much and have smart mouths that get them in trouble. Rucka is particularly good at writing this kind of character; they may lack social graces and be prone to excesses, but they’re crafty and determined. They’re solution-oriented, or at least “end the problem” oriented.

It’s Stumptown (back at Oni), a detective yarn set in the Pacific Northwest, and it gets off to a very promising start. It’s got one of those gender-neutral protagonists, a female private investigator with a lot of qualities that could stereotypically be tagged as male, but there’s no reason they should be. Women can certainly gamble too much and have smart mouths that get them in trouble. Rucka is particularly good at writing this kind of character; they may lack social graces and be prone to excesses, but they’re crafty and determined. They’re solution-oriented, or at least “end the problem” oriented.

Our heroine here gets hired to find a casino owner’s granddaughter. She’s not getting paid, but success will erase her hefty gambling debt (until she builds it up again, one assumes). She’s not the only person on the girl’s trail, and while her rivals are a bit out of sleuth story central casting, Rucka writes them with assurance and some wit. His background in detective prose shows here. He can play with familiar elements and even trot out some hoary contrivances and get away with it, because he knows how to use them. He’s not satirizing or revitalizing P.I. drama; he’s just writing it very well.

He’s helped by the gritty, shadowy but still restrained illustrations by Matthew Southworth, who seems very in synch with the kind of mood Rucka is trying to convey. Characters look right for their milieu, and the settings are evocative. Colors by Lee Loughridge are just right; they really help convey the passage of time in the protagonist’s difficult, complicated day.

*

Rucka’s Whiteout collaborator, illustrator Steve Lieber, is doing terrific work on another genre story in pamphlet form, Underground (Image), written by Jeff Parker. It’s a survival adventure set in a not-quite-mammoth cave in the Appalachians starring a gutsy park ranger trying to protect natural spaces from greedy developers. Three issues are available so far, and it’s a lot of fun.

I find it harder to review pamphlet comics, since there’s less content to consider, but

I find it harder to review pamphlet comics, since there’s less content to consider, but

In Vegetables, this kind of content is relatively minimal. And while I’ve enjoyed it in the past, I was surprised by how much I enjoyed the relative absence of their caustic bickering. The volume starts with a multi-part but still relatively short cabbage battle that’s fairly standard for their showdowns, then moves on to what I can only describe as food pyramid comeuppance theatre. People often bemoan the lack of vegetables in the average diet (when they aren’t wondering how they can possibly consume as many of them as nutritionists recommend), but Kariya and Hanasaki take it to another plateau.

In Vegetables, this kind of content is relatively minimal. And while I’ve enjoyed it in the past, I was surprised by how much I enjoyed the relative absence of their caustic bickering. The volume starts with a multi-part but still relatively short cabbage battle that’s fairly standard for their showdowns, then moves on to what I can only describe as food pyramid comeuppance theatre. People often bemoan the lack of vegetables in the average diet (when they aren’t wondering how they can possibly consume as many of them as nutritionists recommend), but Kariya and Hanasaki take it to another plateau.

At the age of fourteen, Small checked into the hospital to have an apparently benign cyst removed. After two surgeries, he’s left with ravaged vocal cords and a ragged scar running down his neck. That’s the nut paragraph, but it isn’t what the book is really about. Like the growth on his neck, it’s a symptom of something much more insidious and destructive.

At the age of fourteen, Small checked into the hospital to have an apparently benign cyst removed. After two surgeries, he’s left with ravaged vocal cords and a ragged scar running down his neck. That’s the nut paragraph, but it isn’t what the book is really about. Like the growth on his neck, it’s a symptom of something much more insidious and destructive.

I don’t usually feel compelled to write a proper review of every volume of a given manga series. There are too many of them, to be honest, and I’m usually too lazy. I have to make an exception for

I don’t usually feel compelled to write a proper review of every volume of a given manga series. There are too many of them, to be honest, and I’m usually too lazy. I have to make an exception for  Reading the first volume of Svetlana Chmakova’s

Reading the first volume of Svetlana Chmakova’s  It’s impossible to capture the scale and scope of a disaster like Hurricane Katrina, and a smart creator wouldn’t even try. Josh Neufeld is a smart creator, and he’s a talented one, and I like the approach he takes to

It’s impossible to capture the scale and scope of a disaster like Hurricane Katrina, and a smart creator wouldn’t even try. Josh Neufeld is a smart creator, and he’s a talented one, and I like the approach he takes to

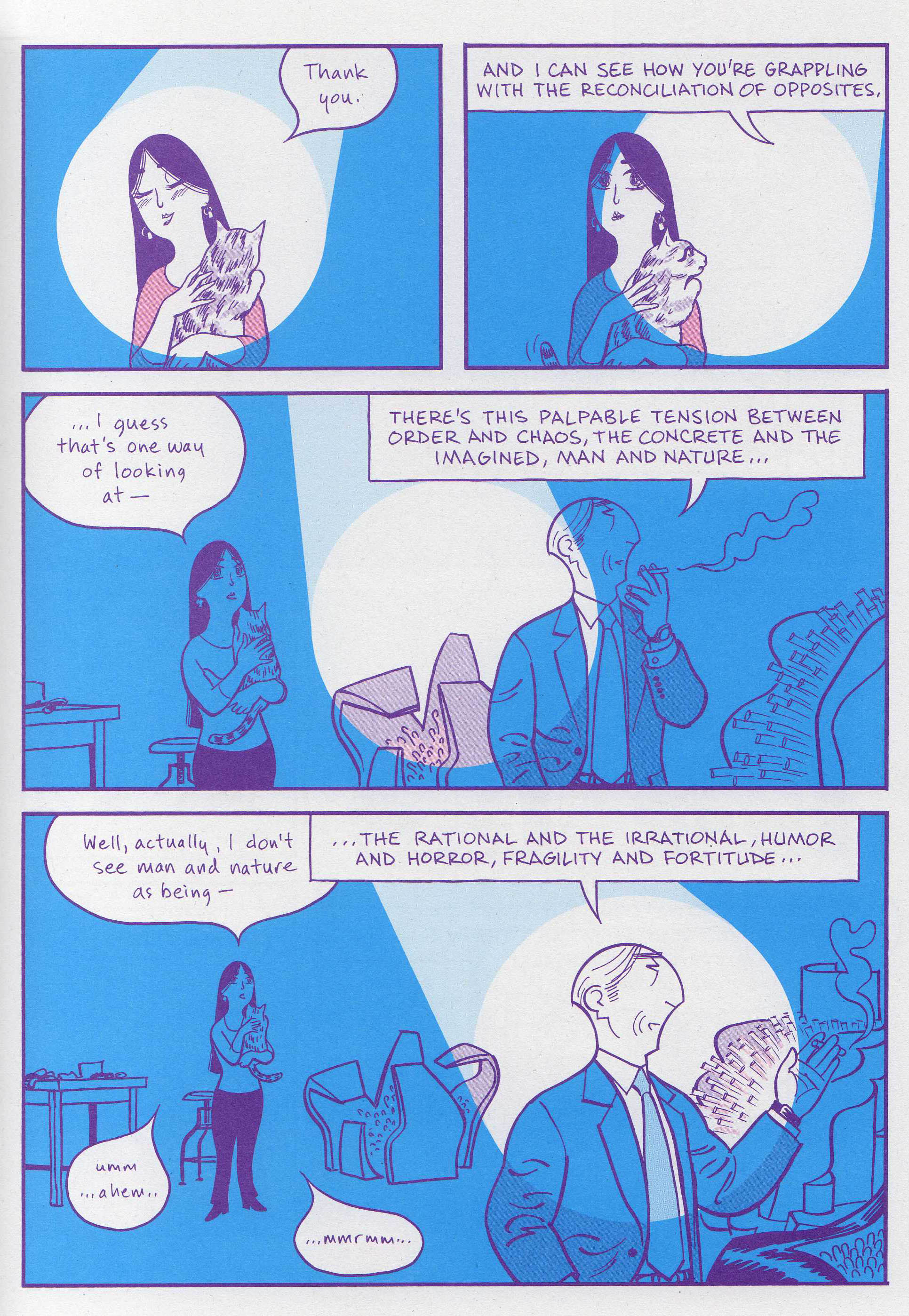

In my experience, tours de force, while breathtaking, can sometimes end up seeming a little hollow. The artistry and technique can excuse the fact that there really isn’t very much underneath. My week has coincidentally ended up being about contemplating books with diversely amazing art. For instance, I found

In my experience, tours de force, while breathtaking, can sometimes end up seeming a little hollow. The artistry and technique can excuse the fact that there really isn’t very much underneath. My week has coincidentally ended up being about contemplating books with diversely amazing art. For instance, I found  Tokumaru is a clumsy jock type. His sister reaches the breaking point with the breakage and insists he join their school’s tea ceremony club to “learn composure and grace if it kills [him]!” The club is run by stoic, dignified Hasune, who may have taken composure a little too far. Nobody who’s read a single chapter of a single yaoi title will be shocked to hear that these very different young men find themselves falling for each other, but Sakuragi does a nice job selling the notion that Tokumaru and Hasune are surprised, and pleasantly so.

Tokumaru is a clumsy jock type. His sister reaches the breaking point with the breakage and insists he join their school’s tea ceremony club to “learn composure and grace if it kills [him]!” The club is run by stoic, dignified Hasune, who may have taken composure a little too far. Nobody who’s read a single chapter of a single yaoi title will be shocked to hear that these very different young men find themselves falling for each other, but Sakuragi does a nice job selling the notion that Tokumaru and Hasune are surprised, and pleasantly so.