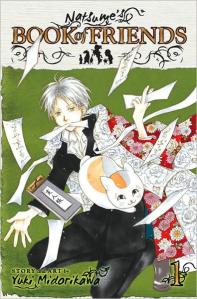

Does the world really need another manga about the husbandry of yôkai, those mischievous, minor demons that populate Japanese folklore? Is there room for more adolescents who can see these creatures and seem fated to interact with them? Sure we do, and sure there is, if the stories are good and the adolescents are interesting and sympathetic. Both are true of Natsume’s Book of Friends (Viz), written and illustrated by Yuki Midorikawa.

Does the world really need another manga about the husbandry of yôkai, those mischievous, minor demons that populate Japanese folklore? Is there room for more adolescents who can see these creatures and seem fated to interact with them? Sure we do, and sure there is, if the stories are good and the adolescents are interesting and sympathetic. Both are true of Natsume’s Book of Friends (Viz), written and illustrated by Yuki Midorikawa.

Orphan Takashi Natsume has spent his whole life wondering why he can see these beings and being pegged as the weird kid, shuffled from relative to relative. There was an escalation in his yokai encounters when he moved to his late grandmother’s village. Takashi never met the lady during her short lifetime, but I’d wager he’d have some choice words for her if he did.

Takashi inherited his yôkai sensitivity from Reiko, his grandmother. She apparently had no other sensitivity to offer as a legacy, having spent her own adolescence challenging yôkai, defeating them, and ensuring their servitude by putting their names down in a book. The yôkai who are pestering Takashi so insistently want their names and independence back, and, since Reiko is unavailable, Takashi will have to do. Learning of his grandmother’s malicious hobby makes Takashi more sympathetic to the yôkai. He takes it upon himself to return their names.

This obviously ends up being more complicated than you’d expect. Some of the yokai aren’t especially appreciative of Takashi’s intentions and would be more than content to take their names back by force. Others have pressing concerns beyond servitude to an angry dead woman. An opportunistic demon named Nyanko (who spends his day in the form of a stuffed cat) offers his protection and assistance with the condition that, should Takashi die during his quest, Nyanko gets whatever’s left of the book.

I like the variety that Midorikawa finds in the premise and the mix of comedy and sentiment in the individual episodes. Her view of the relationship between humans and yôkai is complex, and I particularly love the counterpoint between grandmother and grandson. Reiko turned her isolation and otherness into hostility and control. Takashi turns his into generosity of a sort, or at least into enlightened self-interest. And young Reiko is a sly hoot, even if she is nasty, or maybe because she’s nasty.

Natsume’s Book of Friends doesn’t exactly reinvent the yôkai genre, but it’s got some very promising underpinnings, and Midorikawa’s execution is rock solid.

(Review based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher.)