It must be some kind of testament to the volume of good comics currently in release that I’ve allowed myself to neglect one of the finest. I was trying to make a dent in my “to read” pile and randomly grabbed the third volume of Takehiko Inoue’s Real (Viz). Seriously, what kind of embarrassment of riches are we experiencing that this book can slip my mind, even briefly?

It must be some kind of testament to the volume of good comics currently in release that I’ve allowed myself to neglect one of the finest. I was trying to make a dent in my “to read” pile and randomly grabbed the third volume of Takehiko Inoue’s Real (Viz). Seriously, what kind of embarrassment of riches are we experiencing that this book can slip my mind, even briefly?

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the series, it’s about wheelchair basketball. Well, that’s not entirely accurate. It’s about wheelchair basketball in the same way that Fumi Yoshinaga’s Antique Bakery (DMP) is about pastry entrepreneurs. Real is about people, their choices and struggles, and the means they use to get through the day. Some of these people happen to play wheelchair basketball. That’s more like it.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the series, it’s about wheelchair basketball. Well, that’s not entirely accurate. It’s about wheelchair basketball in the same way that Fumi Yoshinaga’s Antique Bakery (DMP) is about pastry entrepreneurs. Real is about people, their choices and struggles, and the means they use to get through the day. Some of these people happen to play wheelchair basketball. That’s more like it.

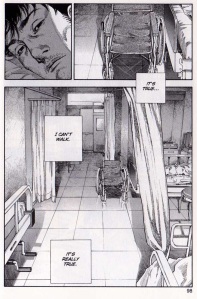

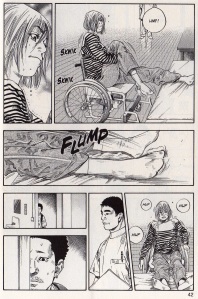

The first two volumes were excellent, but the third goes to an even higher level. It focuses on Takahashi Hisanobu, a high-school athlete and entitled jackass left paralyzed from the waist down after an accident that’s entirely his fault. Needless to say, his expectations are entirely overturned. He’s powerless and frustrated, and he lashes out at everyone around him. But he also begins to take baby steps towards adapting to his new circumstances.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned this in other contexts, but I’m not one to be persuaded by the redemptive power of trauma, where a horrible thing happens to a terrible person, leading that terrible person to become a good person. It always strikes me as at least a bit lazy. Inoue doesn’t reinvent this particular narrative wheel, but he executes it so scrupulously that it’s impossible not to be engrossed. And Inoue is gutsy enough to allow the reader to still think Hisanobu is a jackass, no matter the difficulties the character is enduring.

This kind of material lends itself to melodrama, but it doesn’t feel like Inoue indulges in it. Each moment feels authentic and even understated, even if someone is screaming. It’s riveting to watch Hisanobu’s arrogance mutate into bitterness and to see his mother’s nerves become increasingly frayed. A comic with good intentions can be a mine field of tonal hazards, but Inoue doesn’t step on a one. His execution is almost startlingly poised – not stuffy, or dignified, but utterly economical and expressive.

This kind of material lends itself to melodrama, but it doesn’t feel like Inoue indulges in it. Each moment feels authentic and even understated, even if someone is screaming. It’s riveting to watch Hisanobu’s arrogance mutate into bitterness and to see his mother’s nerves become increasingly frayed. A comic with good intentions can be a mine field of tonal hazards, but Inoue doesn’t step on a one. His execution is almost startlingly poised – not stuffy, or dignified, but utterly economical and expressive.

And honestly, you are unlikely to see a better example of a creator showing instead of telling. Part of me wishes I could see the pages with no dialogue or narration, because I strongly suspect that every essential of the story would still be communicated. The physicality of the characters, their facial expressions and the composition of the pages deliver each beat.

No interest in basketball is required to enjoy Real. You only need to appreciate compelling human drama and splendid comics artistry.

(This review is based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher.)

Motoro Mase’s

Motoro Mase’s

Rise Okitsu and I have something in common. We both loathe her classmates at the prestigious Jyôshioka Gakuen Private High School. We both also harbor a burning desire to go full-on rage monkey on the unbalanced, entitled herd. Poor Rise is too meek, but I’m a prudish blowhard with a blog, so I’m a little freer to express myself about the cast Jun Yuzuki’s

Rise Okitsu and I have something in common. We both loathe her classmates at the prestigious Jyôshioka Gakuen Private High School. We both also harbor a burning desire to go full-on rage monkey on the unbalanced, entitled herd. Poor Rise is too meek, but I’m a prudish blowhard with a blog, so I’m a little freer to express myself about the cast Jun Yuzuki’s

If good taste was all you needed to make millions in publishing, Fanfare/Ponent Mon would be drowning in its own extravagant wealth. They’ve never published a book that wasn’t at least very good, and many of them are exquisite.

If good taste was all you needed to make millions in publishing, Fanfare/Ponent Mon would be drowning in its own extravagant wealth. They’ve never published a book that wasn’t at least very good, and many of them are exquisite.