Ed Sizemore is hosting the current installment of the Manga Moveable Feast over at Manga Worth Reading. This time around, the focus is Yuki Urushibara’s Mushishi (Del Rey). Here’s a Flipped column on the series that I wrote for The Comics Reporter. I’ll be posting more Mushishi-related content later in the week.

*

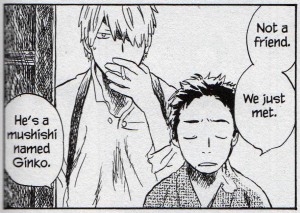

In a chapter of Yuki Urushibara’s elegant, episodic drama Mushishi (Del Rey), master of ceremonies Ginko informs a boy that mushi, the mystical bugs Ginko wrangles, “aren’t your friends. They’re just some strange neighbors of yours.” That’s as nice a tonal summary as anything I can concoct.

Mushi are an ancient part of the environment, and their influences can be extremely malignant to their human neighbors. Mushishi (or “mushi masters”) like Ginko help manage the interactions between humans and mushi, mitigating human suffering when possible. Sometimes no such mitigation is possible, and that’s one of the many intriguing aspects of the series.

Ginko isn’t an exterminator. He’s a scholar and a physician of sorts. He’s also a wanderer in the tradition of Kung Fu‘s Caine, traveling from village to village to learn about little-known mushi and aid and educate their human neighbors. Aiding and educating feel secondary to Ginko’s own quest for knowledge; he’s not precisely mercenary, but he isn’t sentimental or especially altruistic. He isn’t a particularly nice person, and I like that.

I also like that he isn’t entirely predictable. In many of these wanderers’ tales that are more about glimpsing the places and people they visit, the wanderer can be the least interesting element of the narrative, carrying the camera and reacting to what he finds. Ginko certainly fills those functions, but he’s also an agent of change, assessing the situations he finds, divining their sources, and determining appropriate action, if any is actually warranted. In addition to being kind of a grouch, Ginko is also a realist, and not every situation can be fixed in any meaningful way.

Ginko, with his trench coat and ever-dangling cigarette, isn’t on a quest. There’s no fixed end point to his work, as there will always be new things to learn about mushi and people who run afoul of them. It’s a job, and it’s one he’s particularly suited to doing, but he doesn’t demonstrate any pilgrim’s fervor or scholar’s mania. He’s got a matter-of-fact nature mixed with an arch inscrutability that spares him blandness. He also attracts mushi, which keeps him from lingering anywhere for too long.

Urushibara demonstrates great creativity and variety in the manifestations of the mushi. Some scenarios can be quite gruesome and perilous; others are benign and almost pastoral. Her approach is a patchwork of bits of folklore, spikes of horror, an appreciation for setting, an undeniable environmentalist bent, and a keen eye for human nature. Like bacteria, the mushi have no particular motive beyond survival, but their side effects can be terrifying.

Intriguing as the effects can be, Urushibara doesn’t settle for a blend of fantasy and horror; she seems much more interested in viewing the mushi and their effects through the prism of human relationships and society.

In one particularly gruesome story, a strain of mushi devours and impersonates human children, and a mother cares for them with the same fervor she would lavish on her own children. In a gentler but still disturbing outing, a girl is granted the gift of sight by a mushi that lives in her eyes, but things progress to the point that she can never stop seeing, and the gift becomes exhausting. Some mushi have an ironic knack for uniting lovers at an awkward or untenable price. But only some of the tales traffic in monkey’s paw irony; Urushibara is just as taken with quaint, unsettling oddities as she is with life-and-death drama.

Urushibara is not quite the artist she is a writer, but her writing is so deft and subtle that saying she’s not as good at drawing is almost a compliment. The strongest visual elements of Mushishi involve its varied settings. Ginko travels through snow-covered mountains, misty valleys, craggy seashores, swamps, and serene farms, offering a rural visual feast. Her renderings aren’t strictly realistic; Urushibara isn’t composing picture postcards. But the settings are unerringly evocative. They have moods all their own.

There isn’t as much variety in her character design. The people who populate her stories generally look average, even a little fragile in the context of the rural vistas they inhabit. But they are average people living generally simple lives, so the choice is appropriate if not especially eye-catching. And Urushibara does grant them a full palette of expression and emotion.

That isn’t to say that she isn’t capable of some breathtaking flourishes. My favorite comes in the second volume, when Ginko visits the mushishi library. Its frail, fetching copyist is infested with mushi that enable her to do her work. When Ginko’s stimulating presence leads the mushi to act up, the results are stunning. Words fly through the air and leap across the walls. Since the sequence is grounded so well in the copyist’s sad history and her ambivalence, the effect is even stronger.

With intelligent writing and often lovely art, Mushishi is an excellent episodic series. Aside from occasional glimpses of Ginko’s past, there’s little in the way of subplot or undercurrent. The drama is contained in the individual chapters rather than in wondering what happens next or how it will all end. That makes Mushishi a vivid and satisfying read, and also a relatively undemanding one. You can pick up a volume at random and not worry about being lost. So many multi-volume series feel like they demand a level of commitment and investment, but Mushishi lends itself to casual reading. That said, I can’t imagine picking up one volume and not wanting to read the others, at least at one’s leisure.