The overwhelming impression I took away from the first volume of The Summit of the Gods (Fanfare/Ponent Mon) is of maleness. I’m not talking about machismo or swagger, which would be tiresome, but of certain qualities that, fairly or not, are often assigned to a Y chromosome. Author Yumemakura Baku and illustrator Jiro Taniguchi aren’t so much making an argument for that kind of assignment as simply presenting it as a given.

The overwhelming impression I took away from the first volume of The Summit of the Gods (Fanfare/Ponent Mon) is of maleness. I’m not talking about machismo or swagger, which would be tiresome, but of certain qualities that, fairly or not, are often assigned to a Y chromosome. Author Yumemakura Baku and illustrator Jiro Taniguchi aren’t so much making an argument for that kind of assignment as simply presenting it as a given.

It’s about mountain climbers living and dead and the impulses that drive them to risk everything in pursuit of peaks. I will readily confess that those impulses are utterly beyond my comprehension. I enjoy the outdoors, I really do, but when I’ve been in a magnificent natural setting and seen occupied sleeping bags dangling from the face of a cliff, my powers of empathy fail completely. It’s an activity that combines perilous heights, continuous effort and self-imposed discomfort, none of which track with my concept of recreation.

This notion of conquering something that dwarfs oneself is one I ascribe primarily to heterosexual males, which I know is neither fair nor accurate. I’ve known plenty of women who consider a vacation squandered if it doesn’t include the risk of injury and exposure and the onus of carrying out their own waste, but “Because it’s there” will always be the original domain of the straight guy to me. Nothing in Summit of the Gods shakes this association, but nothing in it makes me roll my eyes at the characters that embrace the “Because it’s there” mentality.

Part of this is because Baku and Taniguchi resolutely establish mountaineering as a subculture. The true believers, the ones who live for the peaks, are not normal people. Habu, the climber who consumes the bulk of the creators’ attention, is almost afflicted with a kind of cliff-face Asperger’s Syndrome. He’s so fixated on the idea of climbing peaks that others haven’t or doing so in ways they haven’t that there’s no room for anything else. He quits jobs if they interfere with his climbing, and he alienates other climbers with his bluntness and obsession. Habu is intuitive and gifted, but he’s reckless and he dismisses the contributions of his partners. It’s telling that you can’t quite figure out which quality rankles his fellow mountaineers more, the danger or the snubbing.

It’s also telling that Habu becomes the object of fixation of another character. Years after Habu’s greatest accomplishments in the sport, climber-photographer Fukamachi crosses paths with Habu in Kathmandu. Fukamachi has just survived an expedition to Mount Everest that ended badly, and he encounters Habu when both are pursuing a camera Fukamachi believes belonged to George Mallory, who vanished off the mountain in 1924 during his third attempt to reach its peak. As much as Fukamachi would like to trace the provenance of the camera, he’s equally fascinated with Habu’s career as a climber and what led him to a life of obscurity in Nepal.

It’s difficult to characterize Fukamachi’s fascination with Habu. It’s neither clinical nor worshipful, and it isn’t confined to Habu’s link to the camera. There’s no homoerotic charge to it, or even envy of an alpha male. Habu doesn’t inspire unvarnished admiration; his joy in climbing is difficult to share as it’s so specific and fierce. He’s even pathetic in some ways. While the motivations of Fukamachi’s interest in Habu aren’t clear, the interest itself is credible because it mirrors the ways readers are probably engaged in Habu’s story, even as that engagement mirrors Habu’s fascination with mountains. Maybe Fukamachi wants to discover Habu’s secrets for the same reasons Habu wanted to conquer mountains – because they’re formidable and dangerous and just plain there. It’s an intriguing bit of parallel structure.

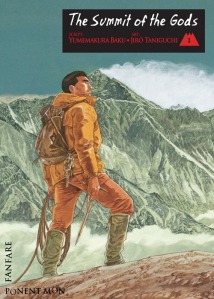

Taniguchi is the ideal illustrator for this kind of material that has both epic scale and intimacy. If the crux of your story is the estimation of landscapes and people, it behooves you to find an artist that can capture the menace and nuance of both, and a writer is unlikely to find anyone better at that than Taniguchi. (As absent as women are from the narrative, it’s nice to read in a text piece that a woman made the collaboration possible, playing matchmaker for Baku and Taniguchi.) Taniguchi is probably the foremost renderer of the middle-aged man that I can think of. They wear their experiences, which is even more evident in a story like this that tracks Habu through the years. Just watching the ways that Habu ages is fascinating. And as far as landscapes and the physicality they demand of puny humans, do I even need to bother praising Taniguchi on that front? Icy cliff faces, Nepalese back alleys, Tokyo urbanity, leafy mountain trails… there’s no setting Taniguchi can’t conquer.

The Summit of the Gods is involving on its own terms as a story of individual evolution and rigorous adventure. It’s more interesting to me in the unobtrusive but pervasive way I read it as being gendered, like a French noun. There’s no value judgment in my observation of that gendering, and I don’t believe the creators were trying to make one about the virtues of a kind of masculine spirit of conquest, but it is a fascinating characterization of a subculture that seems to have born of that kind of maleness. It’s just there.

(This review is based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher.)