Before I get into this week’s license request, I thought I’d belatedly offer my philosophy for this weekly feature. I’m not looking for properties that I think would be commercially viable or even for ones that fill a gap in the cultural or historical record. There are people who are much better qualified to address either of those concerns. My sole consideration is the English-language publication of Japanese comics that I’d like to read. I’m just that selfish.

And really, why else would I request a comic that its original publisher (Shueisha) doesn’t even seem to have kept in print? I’m speaking of the three-volume Children of the Earth, written by Jinpachi (Benkei in New York) Mori and illustrated by Hideaki Hataji. I believe it was originally serialized in Shueisha’s Super Jump magazine, though I can find no mention of the series in the magazine’s Wikipedia entry. It was published in French by Éditions Delcourt under the title Les Fils de la terre. It was among the titles to receive the 2008 Prix Asie awards from the Association des critiques et journalistes specialises en Bandes Dessinées. But information on the book is thin on the ground; no one even seems interested enough in the book to steal it, which is kind of sad.

And really, why else would I request a comic that its original publisher (Shueisha) doesn’t even seem to have kept in print? I’m speaking of the three-volume Children of the Earth, written by Jinpachi (Benkei in New York) Mori and illustrated by Hideaki Hataji. I believe it was originally serialized in Shueisha’s Super Jump magazine, though I can find no mention of the series in the magazine’s Wikipedia entry. It was published in French by Éditions Delcourt under the title Les Fils de la terre. It was among the titles to receive the 2008 Prix Asie awards from the Association des critiques et journalistes specialises en Bandes Dessinées. But information on the book is thin on the ground; no one even seems interested enough in the book to steal it, which is kind of sad.

So why am I interested? Partly, it’s my fixation on stories set in rural Japan. Another point in the book’s favor is its subject matter: agriculture. While there’s a growing level of interest in where our food comes from and how it’s produced, it still strikes me that there’s a shocking amount of ignorance on the subject and a disregard for how hardworking and smart farmers need to be, especially if they want to engage in sustainable or organic production. Children of the Earth promises both; no wonder the French embraced it.

Here’s what I’ve been able to glean of the book’s plot from the remnants of my shaky college French: a newbie with Japan’s agricultural agency is sent to a rural village, Takazono, to help local farmers “reform” Japanese agriculture. The bureaucrat, Natsume, butts heads with a local farmer, Kohei, who has no use for the government’s reformation effort. Natsume is won over by Takazono’s charms and the inherent dignity of farming and dedicates himself to encouraging young people to pursue education and careers in agriculture.

Here’s what I’ve been able to glean of the book’s plot from the remnants of my shaky college French: a newbie with Japan’s agricultural agency is sent to a rural village, Takazono, to help local farmers “reform” Japanese agriculture. The bureaucrat, Natsume, butts heads with a local farmer, Kohei, who has no use for the government’s reformation effort. Natsume is won over by Takazono’s charms and the inherent dignity of farming and dedicates himself to encouraging young people to pursue education and careers in agriculture.

(If anyone has read the book in French or Japanese, please feel free to correct any of the above. Add my language “skills” to the often inaccurate shorthand of solicitation text, and you have a recipe for gross misinterpretation of a book’s content, you know? Ditto my inability to find it on Shueisha’s web site, which I suspect I would find difficult to navigate even with any Japanese fluency whatsoever. I did manage to find it on Amazon Japan, which leads me to suspect I could have found it on the publisher’s page if it was there. To summarize, I have strikethrough functionality and I’m not afraid to use it, so please don’t hesitate to tell me I’m wrong about just about anything.)

Admittedly, the English-reading manga fan need not suffer from an absence of farming comics. The first volume of Moyasimon (Del Rey) was just listed in Previews, promising an opportunity to really get to know the microbes so essential to food production. Viz’s Oishinbo gang always seems to be ready to head out to the countryside to see food at the source. (I want their jobs and their expense accounts, don’t you?) But Children of the Earth seems like it would be right up my alley and, as I said, this is ultimately all about me.

Admittedly, the English-reading manga fan need not suffer from an absence of farming comics. The first volume of Moyasimon (Del Rey) was just listed in Previews, promising an opportunity to really get to know the microbes so essential to food production. Viz’s Oishinbo gang always seems to be ready to head out to the countryside to see food at the source. (I want their jobs and their expense accounts, don’t you?) But Children of the Earth seems like it would be right up my alley and, as I said, this is ultimately all about me.

(P.S. Okay, it doesn’t have to be entirely about me. I’m open to guest authors on License Request Day, so feel free to drop me a line if there’s a book you’re burning to see published in English.)

If you haven’t treated yourself to the first two volumes of Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie’s earthy, charming soap opera set in the Ivory Coast of the 1970s, then you should catch up, since the third,

If you haven’t treated yourself to the first two volumes of Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie’s earthy, charming soap opera set in the Ivory Coast of the 1970s, then you should catch up, since the third,  Top Shelf drops a massive omnibus, available in soft- and hardcover versions, of Eddie Campbells Alec comics, called

Top Shelf drops a massive omnibus, available in soft- and hardcover versions, of Eddie Campbells Alec comics, called  I saw this on Twitter yesterday, and there it is in the catalog. Viz releases two volumes of Inio (

I saw this on Twitter yesterday, and there it is in the catalog. Viz releases two volumes of Inio ( I automatically become nervous when buzz about a book reaches a certain pitch, so I’m glad I read a comp copy of David Small’s

I automatically become nervous when buzz about a book reaches a certain pitch, so I’m glad I read a comp copy of David Small’s  Last, but certainly not least, Yen Press brings boundless joy to the world (at least the world occupied by people with good taste) by releasing the sixth volume of Kiyohiko Azuma’s hilarious, completely endearing

Last, but certainly not least, Yen Press brings boundless joy to the world (at least the world occupied by people with good taste) by releasing the sixth volume of Kiyohiko Azuma’s hilarious, completely endearing  It must be some kind of testament to the volume of good comics currently in release that I’ve allowed myself to neglect one of the finest. I was trying to make a dent in my “to read” pile and randomly grabbed

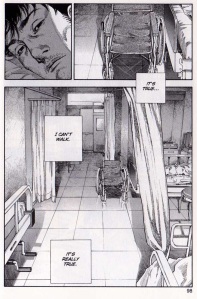

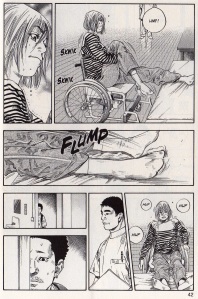

It must be some kind of testament to the volume of good comics currently in release that I’ve allowed myself to neglect one of the finest. I was trying to make a dent in my “to read” pile and randomly grabbed  For those of you who aren’t familiar with the series, it’s about wheelchair basketball. Well, that’s not entirely accurate. It’s about wheelchair basketball in the same way that Fumi Yoshinaga’s Antique Bakery (DMP) is about pastry entrepreneurs. Real is about people, their choices and struggles, and the means they use to get through the day. Some of these people happen to play wheelchair basketball. That’s more like it.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the series, it’s about wheelchair basketball. Well, that’s not entirely accurate. It’s about wheelchair basketball in the same way that Fumi Yoshinaga’s Antique Bakery (DMP) is about pastry entrepreneurs. Real is about people, their choices and struggles, and the means they use to get through the day. Some of these people happen to play wheelchair basketball. That’s more like it. This kind of material lends itself to melodrama, but it doesn’t feel like Inoue indulges in it. Each moment feels authentic and even understated, even if someone is screaming. It’s riveting to watch Hisanobu’s arrogance mutate into bitterness and to see his mother’s nerves become increasingly frayed. A comic with good intentions can be a mine field of tonal hazards, but Inoue doesn’t step on a one. His execution is almost startlingly poised – not stuffy, or dignified, but utterly economical and expressive.

This kind of material lends itself to melodrama, but it doesn’t feel like Inoue indulges in it. Each moment feels authentic and even understated, even if someone is screaming. It’s riveting to watch Hisanobu’s arrogance mutate into bitterness and to see his mother’s nerves become increasingly frayed. A comic with good intentions can be a mine field of tonal hazards, but Inoue doesn’t step on a one. His execution is almost startlingly poised – not stuffy, or dignified, but utterly economical and expressive. I can’t remember if it was in Mad or Cracked or Crazy, but many years ago there was a great parody of Casper, the Friendly Ghost called “

I can’t remember if it was in Mad or Cracked or Crazy, but many years ago there was a great parody of Casper, the Friendly Ghost called “ Updated: I almost never look at the Marvel section of the ComicList, so I missed the listing for the collection of the

Updated: I almost never look at the Marvel section of the ComicList, so I missed the listing for the collection of the  When Ruka was younger, she saw a ghost in the water at the aquarium where her dad works. Now she feels drawn toward the aquarium and the two mysterious boys she meets there, Umi and Sora. They were raised by dugongs and hear the same strange calls from the sea as she does. Ruka’s dad and the other adults who work at the aquarium are only distantly aware of what the children are experiencing as they get caught up in the mystery of the worldwide disappearance of the oceans’ fish.

When Ruka was younger, she saw a ghost in the water at the aquarium where her dad works. Now she feels drawn toward the aquarium and the two mysterious boys she meets there, Umi and Sora. They were raised by dugongs and hear the same strange calls from the sea as she does. Ruka’s dad and the other adults who work at the aquarium are only distantly aware of what the children are experiencing as they get caught up in the mystery of the worldwide disappearance of the oceans’ fish. Motoro Mase’s

Motoro Mase’s  My plan is to concentrate this feature on titles that have never been published in English, but I reserve the right to make the occasional exception and turn License Request Day into Rescue Request Day. This week, I’m inspired by the arrival of Kiminori Wakasugi’s

My plan is to concentrate this feature on titles that have never been published in English, but I reserve the right to make the occasional exception and turn License Request Day into Rescue Request Day. This week, I’m inspired by the arrival of Kiminori Wakasugi’s  Digital Manga Publishing released two of this series’ six volumes in 2005, breaking hearts by not completing the run. (I won’t guess how many hearts were broken; obviously not enough, or it would have been profitable enough to finish.) I won’t pretend that the audience for the book might not be a bit narrower than most. The art is unusual, the protagonist is a horrible person, and the violence and depravity are pretty much constant. Of course, the people whose response to that is “Sign me up!” are loyal sorts.

Digital Manga Publishing released two of this series’ six volumes in 2005, breaking hearts by not completing the run. (I won’t guess how many hearts were broken; obviously not enough, or it would have been profitable enough to finish.) I won’t pretend that the audience for the book might not be a bit narrower than most. The art is unusual, the protagonist is a horrible person, and the violence and depravity are pretty much constant. Of course, the people whose response to that is “Sign me up!” are loyal sorts. She’s kidnapped a horrible child at the behest of some mysterious “Old Men.” The child’s father sets a substantial bounty on Bambi’s head, and there are plenty of seedy types who are more than willing to off a teen for five hundred million yen. Good luck to them, honestly, as Bambi is much more likely to go through than around. Kaneko assembles a vivid, repulsive rogues gallery for Bambi, and one can only imagine what kind of human monsters lurk in the other four volumes.

She’s kidnapped a horrible child at the behest of some mysterious “Old Men.” The child’s father sets a substantial bounty on Bambi’s head, and there are plenty of seedy types who are more than willing to off a teen for five hundred million yen. Good luck to them, honestly, as Bambi is much more likely to go through than around. Kaneko assembles a vivid, repulsive rogues gallery for Bambi, and one can only imagine what kind of human monsters lurk in the other four volumes.